Every year, about 1,000 workers in Michigan suffer an injury in which a body part is crushed. That’s 60 percent higher than the estimate published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics–the federal government’s official count of occupational injuries.

Michigan State University researchers Joanna Kica, MPA and Ken Rosenman, MD used hospital records and workers’ compensation data to identify 3,137 work-related crushing injuries in Michigan from 2013 through 2015. This compares to the federal government’s official estimate of only 1,260 incidents for the same period.

Crushing injuries can involve the upper or lower extremities, the head, neck, abdomen, back, and/or the pelvis. A crushing injury may cause damage to the skin, nerves, muscles and/or bones. The severity of the injury depends on the intensity of the force on the affected body part(s).

Nearly 73 percent of the crushing injuries identified by Kica and Rosenman involved the workers’ upper extremities. About 27 percent of the incidents occurred in workplaces classified as “primary metal manufacturing,” although many industry groups—from construction and agriculture to food production—were represented in the data.

Kica and Rosenman note that during the same three-year time period, Michigan OSHA (MIOSHA) conducted 77 inspections at worksites where these crushing injury incidents occurred. Of the inspections conducted, 74 percent resulted in citations for violations of safety standards. Especially troubling to me was reading that nearly 80 percent of the employers had not corrected the hazard that caused the injury.

The researchers describe, for example, the case of a 35-year-old worker whose right hand was yanked into a pulley system. His hand was crushed, he suffered burns up to his elbow, and was hospitalized for five days as a result. Three months after the incident, MIOSHA conducted an inspection at the workplace. The employer had not installed a guard on the machine or taken other measures to prevent the incident from repeating itself.

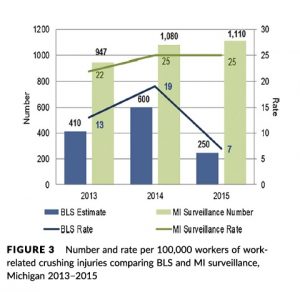

Another discrepancy identified by Kica and Rosenman was the incidence trend between their data and BLS’s estimate. The rate of work-related crushing injuries per 100,000 workers increased from 2013 through 2015 according to the hospital and workers’ compensation data, while BLS’s estimate indicated the decreasing rate. (See figure on left from their paper.)

This is the fourth analysis published by the Michigan State University research team that uses data from several surveillance systems to characterize the magnitude of a specific type of work-related injury. They also use their analyses, which have examined amputations, burns, skull fractures. (here, here, here) and now crushing injuries, to compare their tabulation to the annual injury estimates for Michigan prepared by the Bureau of Labor Statistics. BLS’s data is based on a survey of employers who are asked to report the data they’ve recorded on an OSHA injury log. Kica and Rosenman’s previous analyses found that BLS’s annual Survey of Occupational Injuries and Illnesses (SOII) underestimated the number of work-related amputations, burns, and skull fractures in Michigan by 59, 69, and 54 percent, respectively. Their analysis of work-related crushing injuries found an underestimate by SOII of 60 percent.

Because of research by these epidemiologists and others (e.g., here, here, here, here, here), BLS has been funding projects to examine the reason for the SOII’s undercount. Some are reasons are obvious. For example, BLS only collects data when an injury results in the workers missing one or more days of work. Many injured workers return to work immediately after an injury and given a “light duty” assignment. BLS also does not collect injury data from the self-employed or from farming operations with less than 11 employees. The agency has funded research to interview employers and identify errors in their injury recordkeeping practices, as well as a project to determine the feasibility of including questions about worker injuries in existing national data collection, such as the National Health Interview Survey and the Current Population Survey.

In the meantime, credit goes to Kica and Rosenman for providing a much more accurate picture of the magnitude of work-related injuries and illness, and to the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health for funding the research.