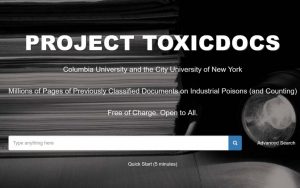

Millions of pages of chemical industry documents are now available on-line courtesy of three public health historians. It’s a treasure trove of information on the efforts by the asbestos, lead, and chemical industries to protect their economic interests at the expense of workers’ and communities’ health.

With just a couple of key strokes on Toxicdocs.org, I was reading a February 1979 letter from Union Carbide to its employees. The firm was telling employees not to be alarmed about co-workers with brain tumors.

“This letter is being sent to you in keeping with our policy to advise you of noteworthy activities at this plant. It is not intended to alarm you nor do we believe there is a cause for immediate, undue concern.”

A few more keystrokes and I was reading a 1979 document prepared by the Asbestos Information Association of North America (AIA/NA) and their demand that OSHA retract a news release. The trade group objected to OSHA’s estimates of the health risks faced by asbestos-exposed workers. In a March 1979 letter to OSHA chief Eula Bingham, AIA/NA wrote:

“[we] must protest in the strongest terms possible such irresponsible and misleading statements.”

I was sucked into Toxicdocs.org. I soon forgot I intended to write this blog post.

Over the last 30 years, historians Gerald Markowitz and David Rosner had amassed an enormous collection of documents. Many were obtained by attorneys through the legal discovery process. Lawyers called up the historians—initially in litigation over childhood lead poisoning—for their expertise in answering the important questions: who knew? and when did they know it?

The documents were essential to their inquiries about corporate behavior. There were boxes and boxes and boxes of records, but so many documents created a professional challenge. Markowitz and Rosner called the dilemma “both a blessing and a curse.”

“…[it] posed a very practical and almost insurmountable challenge to our generation of historians. Throughout most of our careers, documents were sorted by hand and read page by page, as we had done for our lead studies and for the Manufacturing Chemists Association documents. Our exhaustion from the seemingly endless search through the papers limited what we could accomplish.”

In a commentary published in the current issue of the Journal of Public Health Policy, the historians describe teaming up with Merlin Chowkwanyun to address the document-overload problem. Chowkwanyun provided the expertise in using technology “to overcome historians’ previous limits.” But in classic public health style, the effort was not just for their own benefit.

“We found the idea of sharing our primary sources and millions of original pages with students, scholars, and others interested in environmental and occupational health issues particularly exciting.”

Records in the collection include:

- Documents on PCBs from Monsanto’s own corporate archives

- Documents on polyvinyl chloride and petrochemicals from Union Carbide, 3M, Dow Chemical, Du Pont and others

- Documents from the Asbestos Industries Association and the Lead Industries Association

The February 2018 issue of the Journal of Public Health Policy includes invited commentaries about Toxicdocs.org. For example, Stanford University historian Robert Proctor writes:

“We can expect great things from Toxicdocs. The new portal broadens access to crucial traces of corporate malevolence, and in this sense serves as a democratizing force. We will always have bad actors, but now, at least, there is a greater chance that someone will be watching.

“ToxicDocs is like a window opened onto a new and foreign world, a world known previously only to parties in litigation. Archives of this sort give us some very powerful telescopes, and the task is now to learn where they can be most profitably pointed.”

Nicholas Freudenberg at CUNY’s Graduate School of Public Health and Health Policy writes in his commentary:

“While there may still be a place for the nostalgic image of the lone researcher spending long hours in a dusty archive poring over crumbling paper, successful efforts to challenge harmful industry practices will, in the future, require global teams of researchers who can match the breadth of expertise that corporations now deploy to keep their evidence secret.”

The six other commentaries—written by Senator Sheldon Whitehouse (here), the late Jock McCulloch (here), Elena N. Naumova (here), Stéphane Horel (here), and Christer Hogstedt and David Wegman (here)—are equally interesting.

I first became familiar with the work of Gerald Markowitz and David Rosner in 1996 when I read about silicosis in their book Deadly Dust. They peaked my interest in cataloging industry records and using the collection to identify the tactics used by business interests to sow doubt about workplace hazards. Now with Toxicdocs.org, they’ve placed a smorgasbord of records at all of our fingertips. I’m eager to dig in.

GREAT piece, Celeste! We are so very excited about all of this–and hope to hear lots of reports of users’ experiences–eventually what they are able to accomplish by way of protecting workers and communities and the environment. We are open to publishing more about work using ToxicDocs.org in the Journal of Public Health Policy.

Wow! Toxicdocs are amazing website, open-secret docs are open to all. This is like a treasure. I hope this kind of information will not use for people who has hidden agenda. Many original documents are very easy to print and download. Let’s hope for the best. Great post Celeste.

From: Internal Medicine Doctor